A Lion in April

Léo Ferré au Japon

There isn’t a whole lot that connects him. There are other musicians and poets for whom the country makes a more obvious fit. The minimalist composer Terry Riley was marooned at the start of a 2020 world tour by COVID cancellations and regulations. He's still there. Jim O'Rourke has been living in Japan for more than a decade. With both of them, I think, well, yes, that makes sense. There's a healthy enough scene of experimental and avant-garde music with which they make an obvious fit.

So why was I thinking of Léo Ferré and Japan at all? I'd just made the decision to buy an 18 DVD box set of various concerts, tv interviews and appearances. Léo's son Mathieu has been assiduously working through the notebooks, tapes and other archives. For this box set - La Complainte de la télé (1956 - 1992) - it’s noted that the rights eluded him on a few French sources as well as various German, Tunisian and Japanese tv appearances.

Japanese sources? I didn't even know that Ferré had made it there. He did. In 1987. And there you go, an interview with Shimizu Yasuko/清水康子. It's in French, with Japanese subtitles, so perfect for me, perhaps not so good for you.

NOTE: On rereading, I paused here and wondered how it’d be going if you had no idea Léo Ferré was. He’s not exactly a household name outside of France, if indeed even he is there anymore beyond people of a certain generation. For this piece to be ideal, I should be selling you Ferré, whereas I really think you’re capable of working that out for yourself. Will he make me friends or find me lovers? Will I impress if I namedrop? Would I wear the t-shirt? Well, I would…

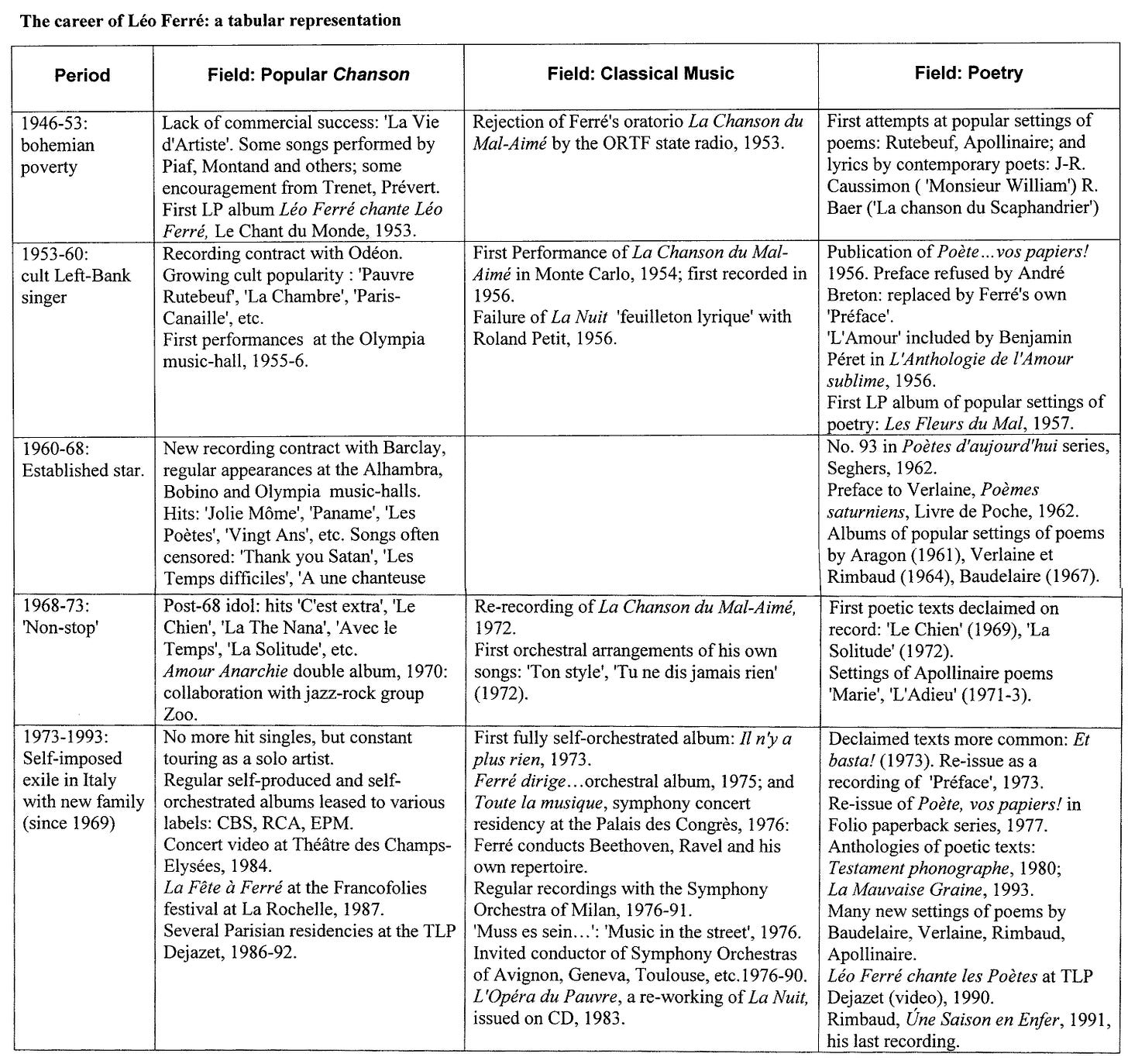

You can do the usual of Wikipedia and YouTube to get a rough feel. This chronological table from “The career of Léo Ferré: a Bourdieusian analysis” by Peter Hawkins might prove informative for some aspects of the following. Otherwise, onwards!

The French Culture Series presented by Shimizu was one slice of state broadcaster's NHK’s French language learning programming at the time. I haven’t lived in Japan for an extended period for a while now so I’m not sure what domestic NHK is like these days, but when I first went to Japan in 1994, there was still a fairly healthy amount of such language shows. On first glance, NHK seemed rather like the BBC with its strong educational remit. The BBC abandoned their foreign language courses in 2005. Their Japanese Language and People series from 2002 was one of the last such undertakings by the broadcaster.

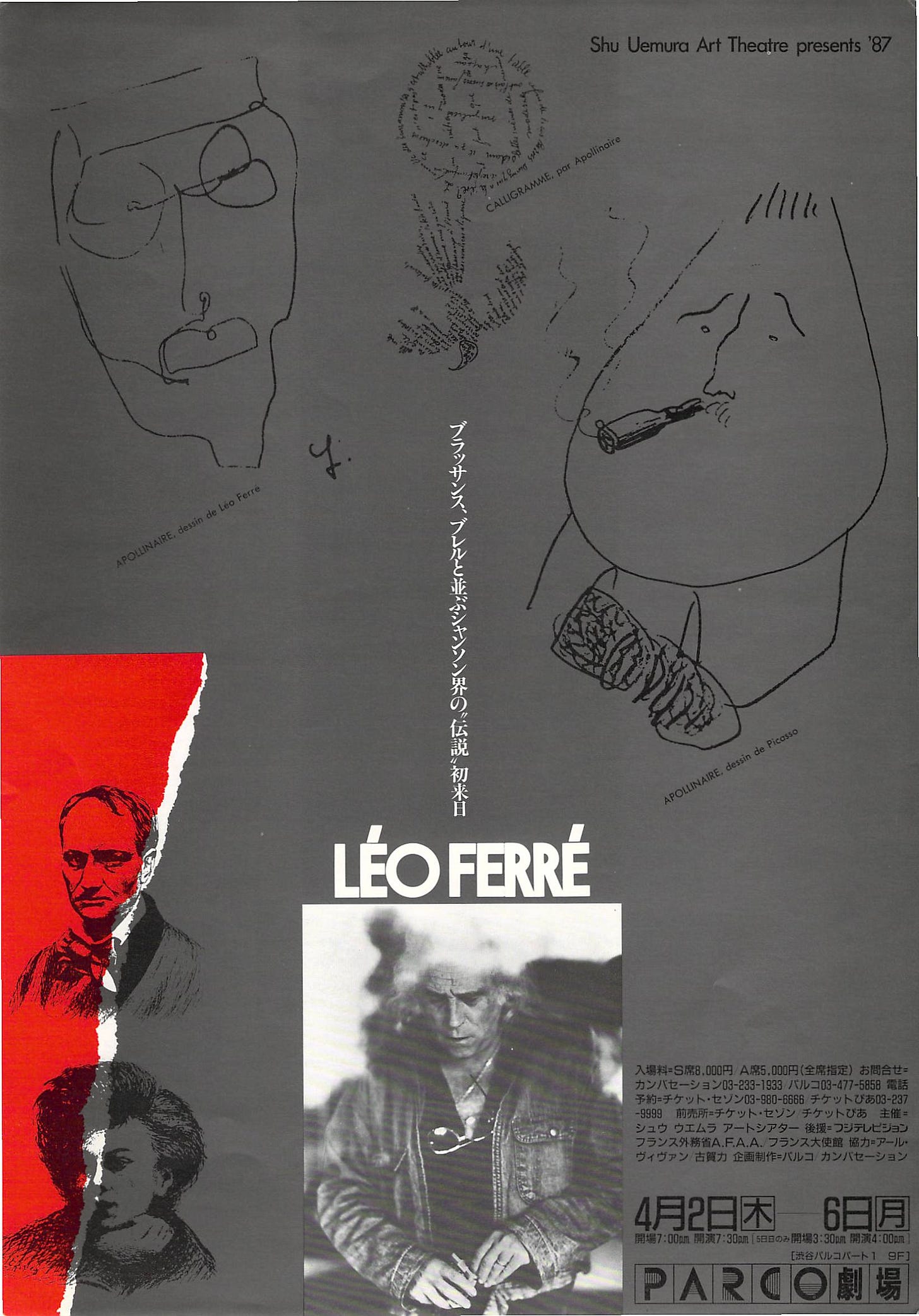

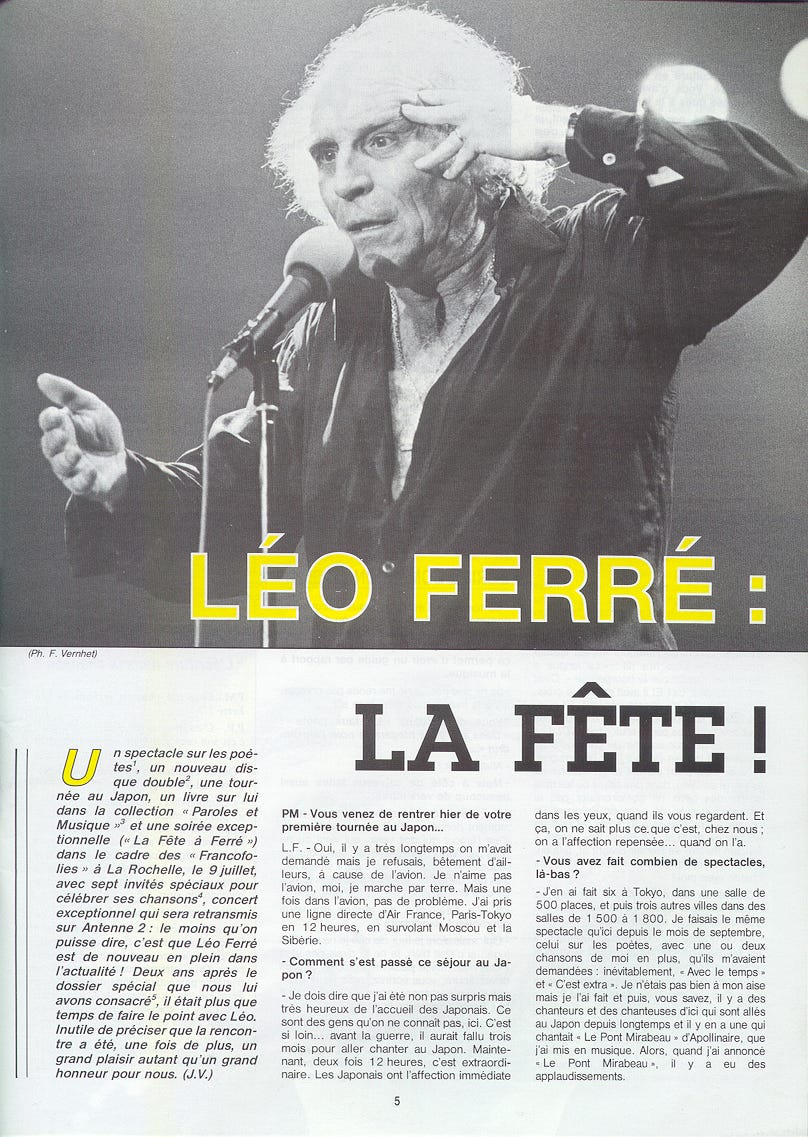

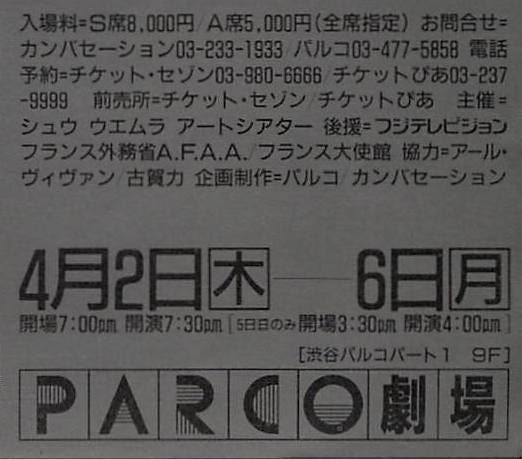

Ok, so why was Ferré in Japan? He was, of course, on tour. Although I've got a reasonable collection of books by and about Ferré, there's not much information about this Japanese tour in them. He played Toyko, Yokohama, Osaka and Akita in some order or another. I then found the two sides of a flyer for his appearance from April 2 to 6 on the 9th floor of the Parco department store in Shibuya, Tokyo. The central catchline above his head mentions this is the first ever Japan appearance for Ferré, one of three legends of French language chanson, and alludes to the famous informal radio interview summit of January 1969 together with Jacques Brel and Georges Brassens.

The photo used for Ferré is from the cover of his 1980 album La Violence et L'Ennui. Violence and Boredom. He's fishing another Celtique out the packet. This now vanished brand of French cigarette was Ferré's preferred. A plumper cigarette (gros module) with a heavier hit than Gitanes or Gauloises.

In the interview with Shimizu, he recounts how in his early days singing in Paris he one day found himself rich enough to buy an entire carton of them, rather than a singular packet. When the brand was withdrawn from sale in the late 1980s, Ferré was by then at a sufficiently greater level of wealth to buy up the remaining stock from individual tabacs so that he might never run out of them before his death in 1993, aged 76. Quand je fumerai autre chose que des celtiques, as he once sang, considering this forthcoming snuffing out of all flames. When I’ll smoke something other than Celtiques.

La Violence et L'Ennui was something of a return to form for Ferré or at least a more unbridled expression of disquiet and anger at the world around him. But the left-hand margin on the reverse of the flyer mentions some of the songs he will be performing and it's not so much this later declamatory longer form Ferré they'll be getting:

Paris canaille

Avec le temps

L'etang chimerique

Le flamenco de Paris

C'est extra

Pont de Mirabeau (Apollinaire)

L'invitation au voyage (Baudelaire)

Chanson d'automne (Verlaine)

Est-ce ainsi que les hommes vivent (Aragon)

Le Bateau ivre (Rimbaud)

Le temps du tango (Jean-Roger Caussimon)

So it's a smattering of his own hits, together with his well known settings of French poets, perhaps better known to the Japanese audience via covers by Juliette Gréco and others. The Rimbaud is a late addition from his 1982 triple album Ludwig-L'imaginaire-Le Bateau ivre where the song clocks in at around 13 minutes, but the others are again from earlier in his career.

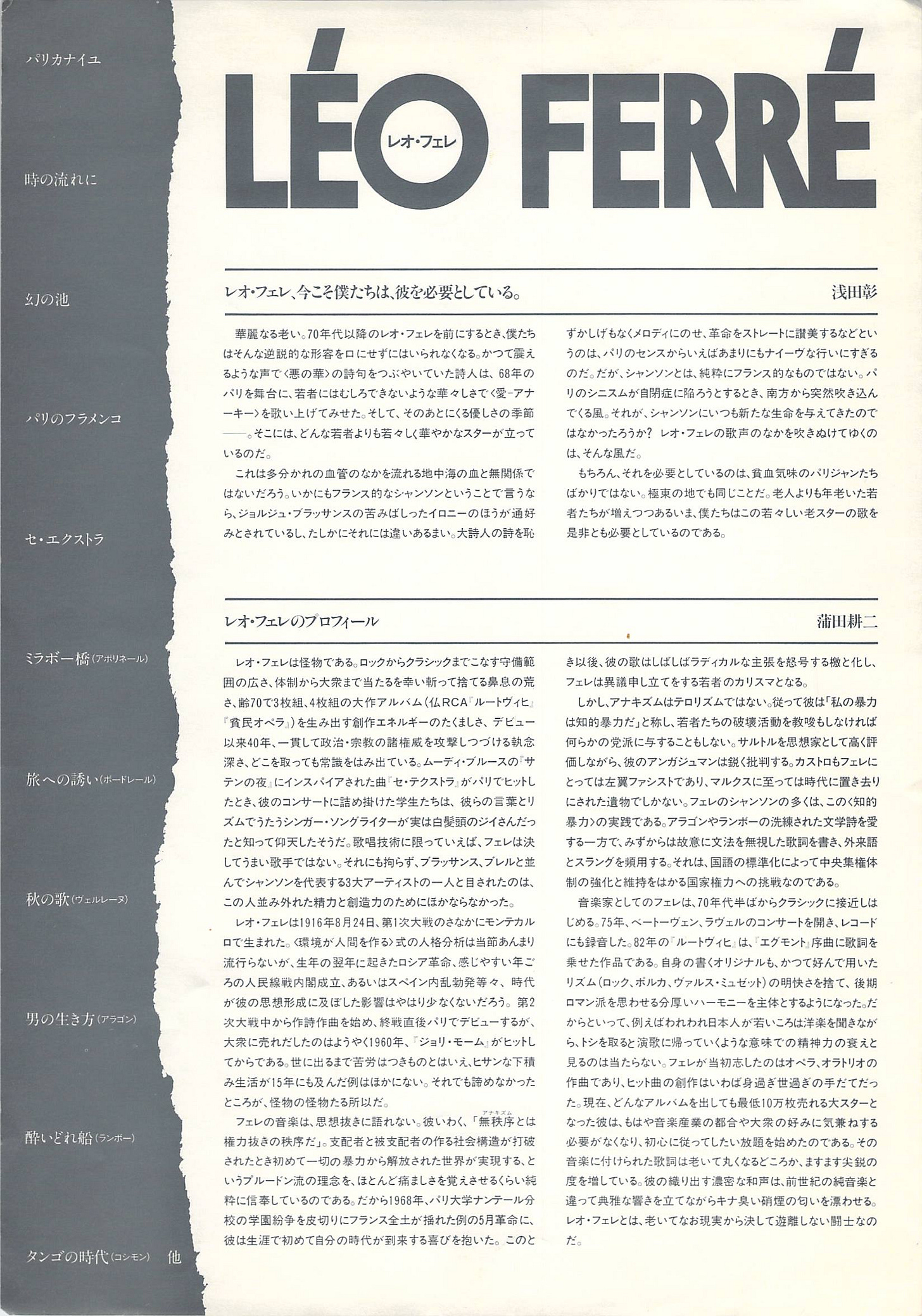

There was an accompanying text published in Japan for the tour entitled Léo Ferré chante les poètes that included Japanese translations of the material performed. As far as I can establish, Léo performed alone, either to taped backing or accompanying himself on piano. He’d been touring a similar poet-centred set around this time in France. More about this book in due course.

The cultural influence of Japan on France - all that Japonaiserie, missus - is more celebrated than what France became in Japan. It's a big subject. But in brief, and with a very rough shorthand, France was one of several national blueprints for Japanese reform and modernisation from the time of the Meiji Renovation of 1868 onwards. Much of this connection was more formal, such as the silk trade or military technology, some of it less so. In return, Japan got Pierre Loti's Madame Chrysanthème. Surely, some mistake...

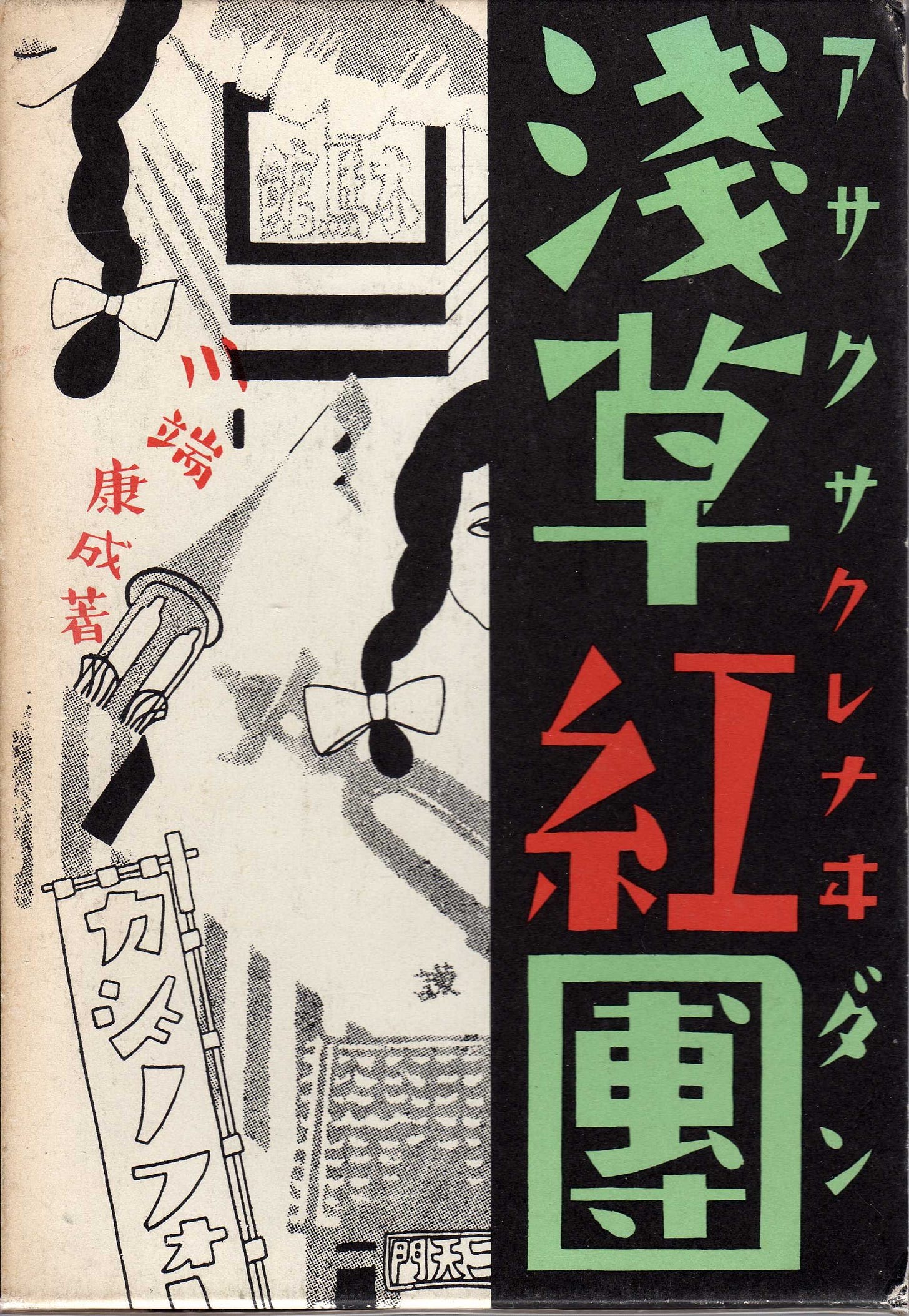

French chanson was not an unknown cultural form in Japan in 1987 when Léo pitched up. Quite the opposite. It had been performed in Japan from the 1920s onwards: the Casino Folies of Asakusa, the Moulin Rouge of Shinjuku and the all-female Takarazuka troupe were inspired and modelled after the Parisian revues of the era and concurrent with the years of Josephine Baker, Mistinguett and the rest. Chanson was a significant influence on the development of modern Japanese popular song or ryūkōka/流行歌.

NOTE: If you don’t know Tokyo, the distinctions of flavour between various districts around the city can be fairly opaque. It is enormous and there are many concurrent centres. The cultural heyday of Asakusa is in this period of the 1920-30s. Asakusa is proletarian and potentially revolutionary. Ginza is sophisticated and pricey. East End vs West End. Shinjuku comes into its own after the war and the tawdry, countercultural focus shifts here from Asakusa. Shibuya develops later from the 70s as a new centre of youth consumption.

Come the 1950s, Japan was anxious for new forms of distraction, dreaming and escape. There is a lot going on musically at this time, but chanson has a sizeable area staked out by its enthusiasts. Ashino Hiroshi/芦野宏 is perhaps the best known of these Frenchie popularisers. I rather like former Takarazuka singer Koshiji Fubuki/越路吹雪. There are many others.

Below is a scene from Warm Current/暖流, a 1957 film by Masumura Yasuzō/増村保造, with Miwa Akihiro/美輪明宏, sometime lover of Mishima Yukio and later voice-over artist for Studio Ghibli. Miwa is too great a presence to describe adequately here, but indicative of the connections between the cabaret scene and the avant-garde and the distinctly French flavour to much of this period.

(I once attended a performance in Osaka by Miwa for a revival of Black Lizard/黒蜥蝪, a play by Mishima based on an Edogawa Rampo story, also filmed with great camp by Fukusaku Kinji/深作欣二. There wasn't an empty seat in the house. The theatre held about 2,000. I was the only evident man in attendance. Or presenting myself as such. It was a steamy evening and I sweltered in a three piece suit, but I hardly felt I could pitch up to see Miwa in shorts and a t-shirt. Note: I never wear shorts)

Various French singers toured Japan during this period and established Japan as an important locus for their careers. An obvious example would be Charles Trenet including Japanese language translations of well known songs such as La Mer.

The first Japanese release for Ferré was a 1956 Yves Montand cover of Flamenco de Paris. His own Fleurs de Mal album of Baudelaire’s poems came out in 1958, just one year after its French release. More follows, such as a cover by Yvette Giraud of Le Pont Mirabeau, his setting of Apollinaire's poem. Giraud toured Japan on numerous occasions.

See also Kaneko Yukari’s later cover of the same.

Later, it's impossible to imagine the ever-black ever-smoking Asakawa Maki/浅川マキ without Juliette Gréco. Maki of course connects to Terayama Shūji/寺山修司, the poet and theatre director who supplied the words to much of her early material. Terayama died in 1983. I can't help but wonder who Ferré met when he was in Japan. Did people connect him to the embers of the Japanese underground and avant-garde or was it just chansons enthusiasts keen to dream of that illusory Left Bank of departed lovers and midnight bridges.

In other words, did Japan want classic Ferré over Ferré as immense provocateur or monstre sacré? The first and Léo seems happy to have provided such. There's no shortage of anarchists in Japan. Did he meet any or was his time there all rather hustled from hotel to venue to restaurant to hotel, etc. My own experiences living and working in Japan tend to make me think that his itinerary would be fairly busy. You might want an afternoon or day off just to wander around or stay in bed to get over jet lag, but the organisers would feel this was a dereliction of duty and care. I doubt Ferré would be that easy to corrall! But I wonder just how his days went by.

There are some slight clues as to this in an interview in Paroles et Musique on his return. This is from leo-ferre.eu, an exhaustive scrapbook site of Ferré activities ad such that is well worth visiting if you're a fan.

The little books he mentions are copies of Léo Ferré chante les poètes mentioned above. This is a 137ish pages with a vinyl cover. It contains a few essays by Ferré as well as translations of the various works he might be performing on any given night. These are by Kubota Hanya/窪田般彌, a professor at Waseda, known particularly for his work on Apollinaire and other Symbolists as well as translating the Memoirs of Casanova. I've ordered a second hand copy of the Ferré book from Japan but it might be a while before it turns up here.

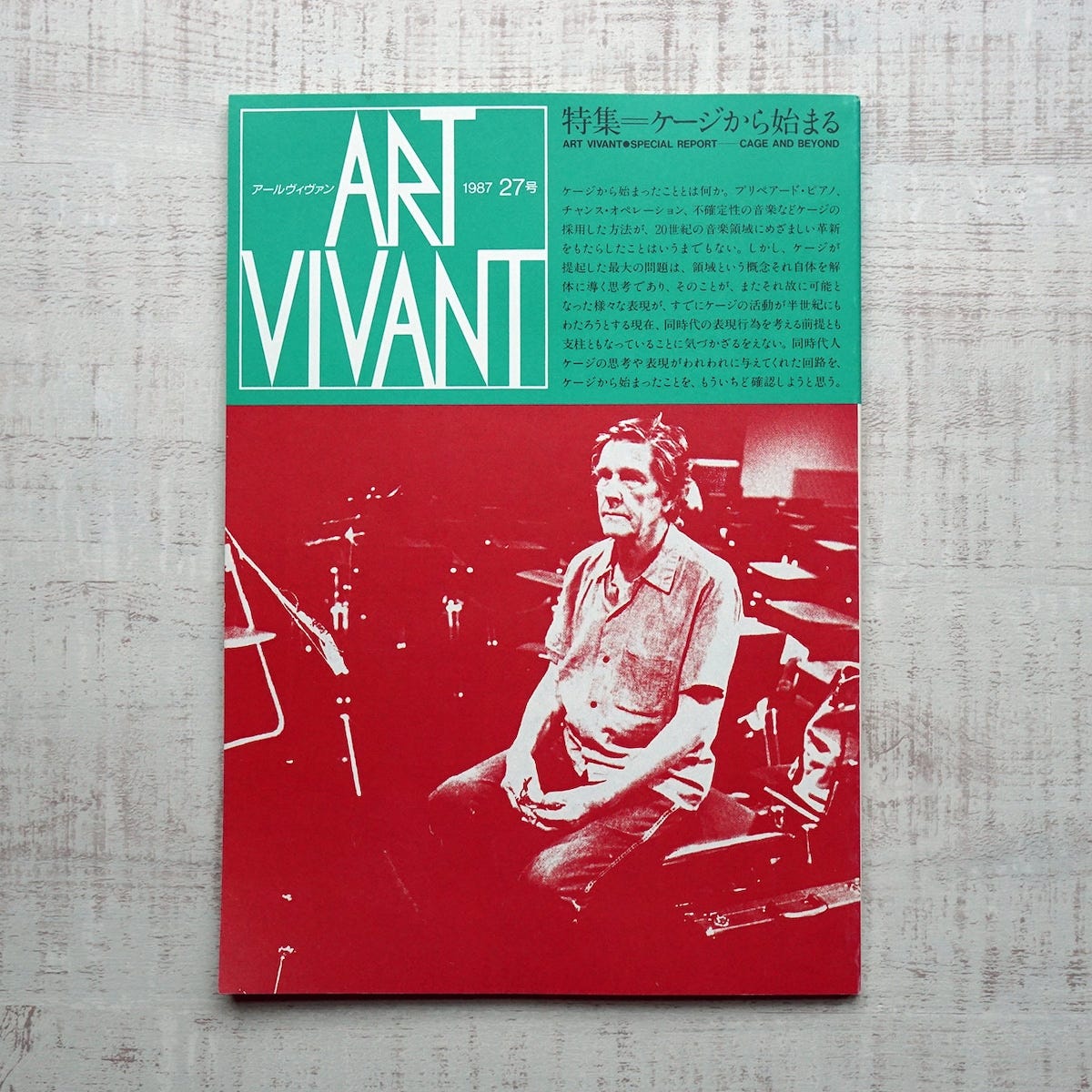

The publishers are listed as New Art Seibu/ニューアート西武 and Art Vivant/アール・ヴィヴァン. Aha! This ticks a number of boxes once you compare that to the flyer. Léo Ferré in Japan is Parco-Saison Culture. The publisher, the venue and the shop where it is located are all part of the Saison group headed by Tsutsumi Seiji/堤清二.

A number of things have been happening in Japan. The post-war era of protest and radicalism has been neutralised. This is generally dated to the Asama-Sansō siege of 1972 where the Japanese state and remnants of the United Red Army face off. State wins, obviously. The complement to those political energies, such as various avant-garde artists and theatre groups, are increasingly neutered or recuperated into the mainstream.

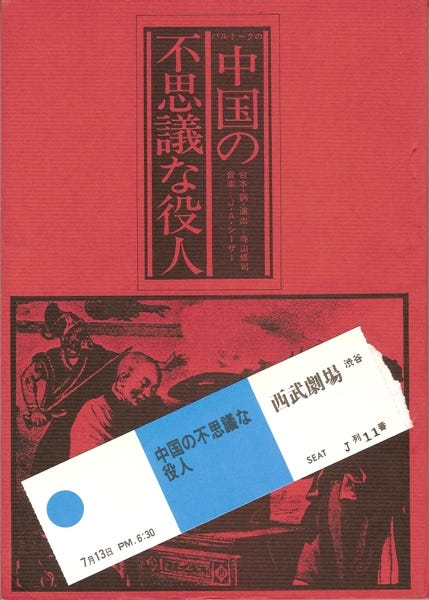

Shibuya Parco opened in 1973 and the theatre where Léo performs was at that time known as the Seibu Theatre/西武劇場. It looks like the main sponsor (主催/shusai) is the Shu Uemura Art Theatre. Oh, if only Léo had done a series of make-up adverts for the brand! As if…

In that close up above, there is also the mention of Fuji Television along with the French Embassy and the Association Française d'Action Artistique as backers (後援/kōen), which suggests that some of the performances or tour may have been recorded for potential broadcast.

NOTE: It’s worth pointing out that S seats for the concerts are ¥8,000 and A seats are ¥5,000 which seems to me about the same price you’d be paying today. Cheap it isn’t.

The Parco theatre had strong links to the avant-garde scene. Terayama's own Tenjō Sajiki/天井桟敷 theatre was located in Shibuya at this time and sometimes performed there. Parco, in all its various forms and offshoots, was shifting the focus of (youth) culture away from Shinjuku towards Shibuya. You might have gone to Shinjuku to plan lobbing some figurative pavés at the cops back in the day, but come the 70s onwards, you were increasingly heading to Shibuya to go shopping. Consumption was the new happening. Whereas London's own Biba had been a spectacular while it lasted failure, Parco was a success or at least it was sufficiently buoyed by the nascent Japanese economic bubble to indulge its vision. Much better minds that my own have written extensively on this subject. More here and, in Japanese, here and here.

Parco Shibuya had its own gonzo shitposting avant la lettre subculture magazine Bikkuri House/ビックリハウス from 1974 to 1985, founded by two former members of Terayama's troupe. The New Art Seibu mentioned in Léo's book connects to the Ikebukuro store of the Seibu chain where the Saison Museum of Art opened in 1975. Art Vivant was the in-house art bookshop, as well as a noted record specialist, and published its own art magazine from 1980 to 1989. If you come across either of these titles second hand, they are well worth buying. The issue around the time of Léo's tour was devoted to John Cage.

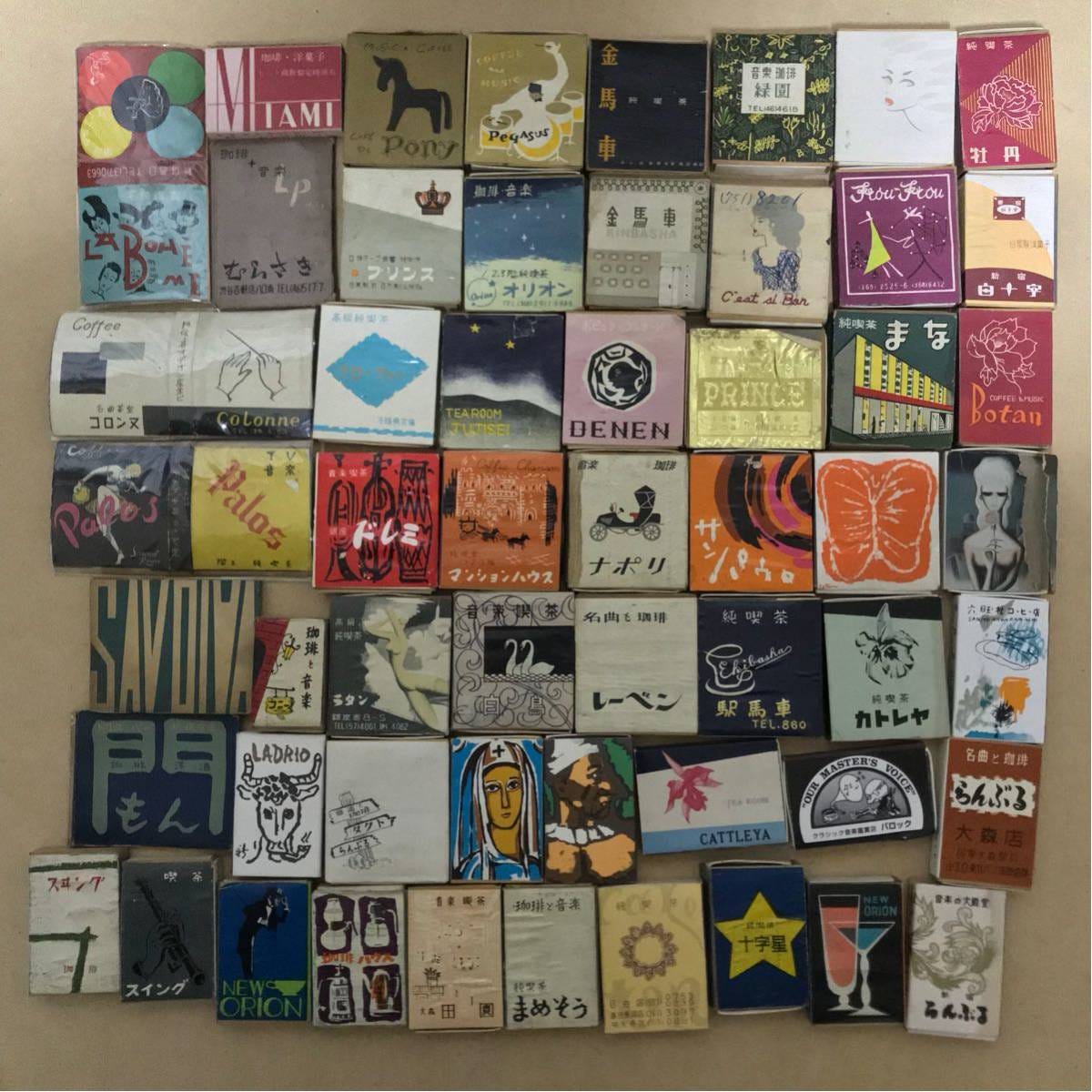

One further name that pops up for cooperation (協力/kyōryoku) alongside is Koga Tsutomu/古賀力. He had started out as a performer at Ginpari(s)/銀巴里, a legendary "chambre de la chanson" café in Ginza which opened in 1951. This venue was one of several at the forefront of the post-war kissaten/喫茶店 boom, cafés which were often themed around the musical interests of the owner. These are invariably private, enclosed spaces. Lots of dark wood. Like an old school pub, you can't really see much in through the windows.

Some of these, the meikyoku kissa/名曲喫茶, are known for their exceptional hifi systems where you feel conscious that your coffee slurping might be upsetting the other reverential customers. Other kissaten can be rather more forgiving about having a conversation. Most, until recently, were fully smoking. Many still are. Smoking restrictions in Japan are on the whole the reverse of our own. They don't want you smoking out on the street as you walk about. Better that you're inside. And being inside will generally cost you ¥500 or so for that cup of coffee and those moments of escape.

Another form of this coffee culture were the utagoe kissa/歌声喫茶. Cafés where people would meet to sing folk songs, often with a proletarian revolutionary edge of protest. This is of course some years before the advent of karaoke. These were often Russian themed, such as Katyusha/カチューシャ in Shinjuku. Russian song is another significant strand of genre alongside French chanson in Japanese music. Swanky Ginza, however, is not Shinjuku and Ginpari was I suspect a bit more rarified with its uptown clientele of Miwa and Mishima, possibly playing footsie, and so on.

In 1968, Koga had opened his own chanson place in Akasaka called Boum/ブン. Akasaka is a pricey area not to be confused with Asakusa! It has a long history as an entertainment district and is conveniently located for princes, politicians and others. Charles Trenet, Charles Aznavour and Juliette Gréco had all performed or visited here at Boum. One of the very few images of Ferré in Japan can be seen below as the camera pans through the photos. A choice turquoise shirt. He signs the wall.

I can imagine that Koga may well have been put forward or suggested himself as someone who could provide some French-speaking support for Léo over the course of his Tokyo stay. And where did he stay? I've been pondering that for a while. Given the Parco-Saison-Seibu etc link, I can't help but assume they'd put him up in one of the numerous hotels they had a finger in. You wouldn't put him up in the New Otani or the Okura. The obvious choice for the period would be the Akasaka Prince, as the Prince chain are part of the Seibu group.

The hotel dates from 1955 and had recently undergone the construction of a 40 floor tower courtesy of Tange Kenzō/丹下健三 that was completed in 1982. The Prince was quite the place at the time and Akasaka would be an easy enough taxi ride along the 246 through Aoyama, Omotesando and into Shibuya proper. There was also a top class French restaurant on site, Le Trianon, as well as the Napoleon Bar. And if Léo fancied a glass or two after hours offsite with Francophones, he could swing by Boum. Perfect.

(And so, finally, I get to the point of this piece! It might only have taken half an hour to find out some of the stuff above, but it takes longer to try and explain the background.)

I imagined Léo at Boum one evening. Another successful night at Parco. He fancies heading straight back to the hotel. Jet-lag marks these early Japan nights and days. They neither feel like one nor the other. Koga appears and lets him know there are some guests expected tonight he really should meet. Oh, okay... Taxi!

Several glasses later, he's tiring. It's hard to concentrate on the conversation around him. It's taking more and more effort to comprehend the Japanese-accented French. He lights another Celtique to try and sharpen his senses. After some encouragement, he takes to the piano. A poet must sing for his supper. There's most likely a dish or two on offer, probably boeuf bourguignon with a toasted garlic baguette. But what to sing? Well, enough of this accordion background I've been tolerating, I'll wake them up. He improvises an accompaniment to Le Chien. A song from 1970 that marks a break with classic chanson into a freeform period of intense, impassioned declamatory, spoken word pieces. If you want the psychjazz noodlings of ZOO accompanying the 1970 recording, try here, but this more muted sepulchral version is exceptional.

Silence. Then applause. He shrugs and blinks. Well, it really is about time, I've an interview for NHK in the morning. I'll get you a cab, says Koga, as they walk outside. No, no, replies Léo, I'd like some fresh air. It's April. The nights are not so cold. And look, Léo points towards the distant tower of the Prince that rises above them, I have my Bethlehem star. Koga watches him depart. The old fool will get himself lost.

Soon enough he is. Anyone who has lived in Tokyo or elsewhere in urban Japan will know that these streets and lanes do not observe Cartesian regularity. You think a right turn followed by a quick left should bring you out there but generally it doesn't. Late at night, spirits and demons, if not determinedly malignant, these playful tricksters, off-piste geographers who bend time and space so you feel you might never get home, they lead you to places that you will never find again by daylight.

This is of course what happens to Léo and I can see him, a wild-haired bunraku puppet, maybe one of those who sheds human form mid-performance to reveal that he was something else all along. A dog, a monkey, an owl. This body is my own, but I am not moving it - shadow operators, puppeteers - these words are mine but I am not speaking them - chanters, tayu/太夫, recite them from little books - the road is leading towards that distant bridge. Ah, Le Pont Mirabeau! But beware, just as you never go to a river in a folk song, bridges here will lead you across to the underworld. Mountain shamans mumble their conversations with the dead. Don't go, Léo! Do not pass beyond.

Maybe in a more Parco-Saison world, I could pitch this brief daydream as a part-bunraku, part-animated film and there'd be some seed money for development. Not exactly a juke box musical, but one that could take in a few songs along the way. I'm a big fan of bunraku puppet theatre, but you can only experience it in situ. Productions very rarely tour outside Japan given the expense. It was a significant reason for me to choose Osaka as a place to live after some markedly dissolute Tokyo years. There'd be a new production season every couple of months. The special performances for children were especially enjoyable as they were rather more free with their content and not stuck in the classic repertoire of Chikamatsu Monzaemon/近松門左衛門 and others.

I then remembered there was an Edith Piaf bunraku crossover five years ago so I can hardly claim this format as my own! Although in mine, during some meld of Paris 68, the Commune, Anpo protests and red helmet students, there would arise above the city the figure of Pepée, the former circus chimpanzee (“with Gainsbourg’s ears”) Léo had adopted in 1961 and was later shot in April 1968 in Léo’s domestic absence for her unruly, dangerous behaviour towards pretty much everyone else. That death - for Léo, an assassination - produced one of his greatest love songs and was the far greater tumult in that year than anything going on dans la rue.

This is a vanishing world. The Shōwa era of Emperor Hirohito ended in 1989. Ginpari closed in 1990. Bun in 2011. Tange's Akasaka Prince was demolished in 2013. Parco Theatre disappeared in 2016. Chanson still has a cultural presence in Japan, but it’s assuredly nostalgic rather than living.

Ferré arguably saw the best of Japan in 1987, before the collapse of the bubble at the start of the 90s and the stagnation that followed. At least, it was certainly a Japan which its inhabitants were keen to show off and could feel rightly proud about. They had made something of a wonderland over those forty years. Was it too good to last? Was it built on shady deals and backhanders? Absolutely. Was it corrupt? For sure. But corruption does not mean that there is a shortage of rules to learn and follow. There is no lack of regulation or order. It works. It provides. More or less. Why question it?

How much did Ferré know or grasp of Japanese politics? Particularly those radical years of protest and opposition in Japan that very much mirrored (sideshow style perhaps) the post-war era in France. Without doubt, he could see the lassitude of France post-68 and the failures of the radical left as much as the exertion of authority and control in novel beguiling forms. He was of course a self-professed anarchist, as was Brassens, a position which allowed him expression with no regard to party lines and loyalties. One famous bon mot in search of reaction: "La gauche est une salle d'attente pour le fascisme". The left is fascism's waiting room.

Ferré's anarchism is not so much that of, say, the CNT in revolutionary Catalonia. It's not one that is focused on the production of practicable solutions or long historical examinations over the where and what of Makhnovism and so on. I'd suggest he's critical of this anarchism also, in that it is the exercise of power and authority that the anarchist must oppose and struggle against. Anarchists are not immune to becoming cops themselves given the chance. For a period in the 70s, his concerts were often attended by a vocal group of leftists and others who would try and shout him down as a bourgeois pretender disinterested in direct engagement.

One rumour - I've heard similar myths about others! - has him touring in his Rolls Royce or Ferrari but changing over to a more acceptable Citroen as he approaches town. Perhaps. He certainly wasn't President Jose Mujica in Uruguay and his Volkswagen.

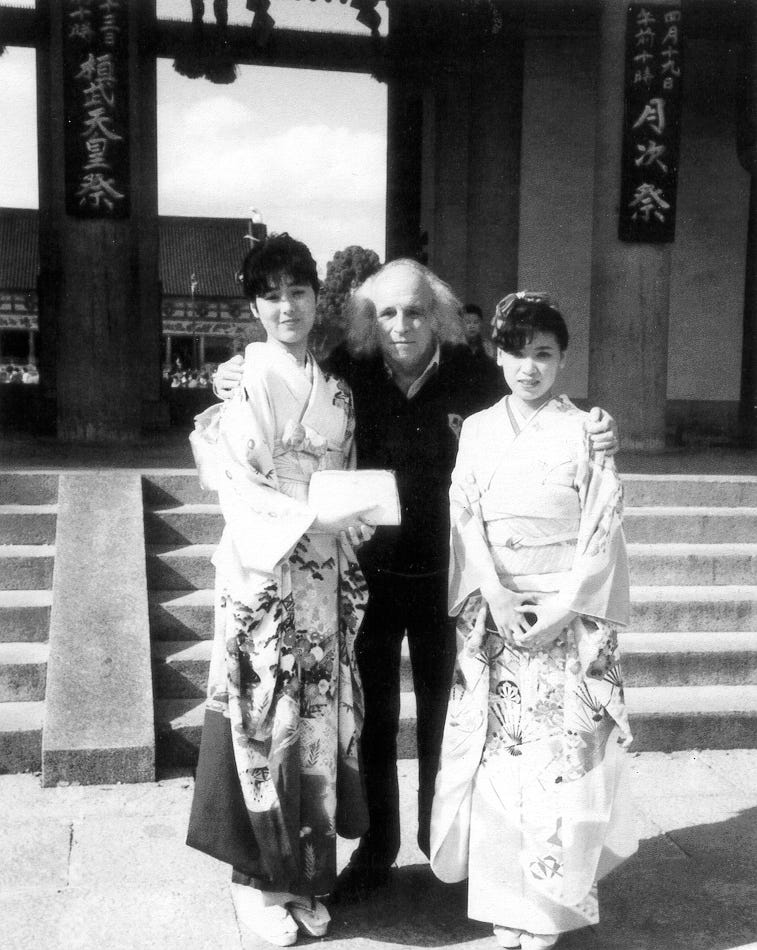

Aside from a couple of shots at Bun, the only photograph I’ve found of him in Japan is here. One of those slightly uncomfortable shots, too obvious, lurching between two young women. The pillar to the left announces the Emperor Jimmu Festival on the 3rd (April). The pillar on the right has a New Moon Festival on the 19th.

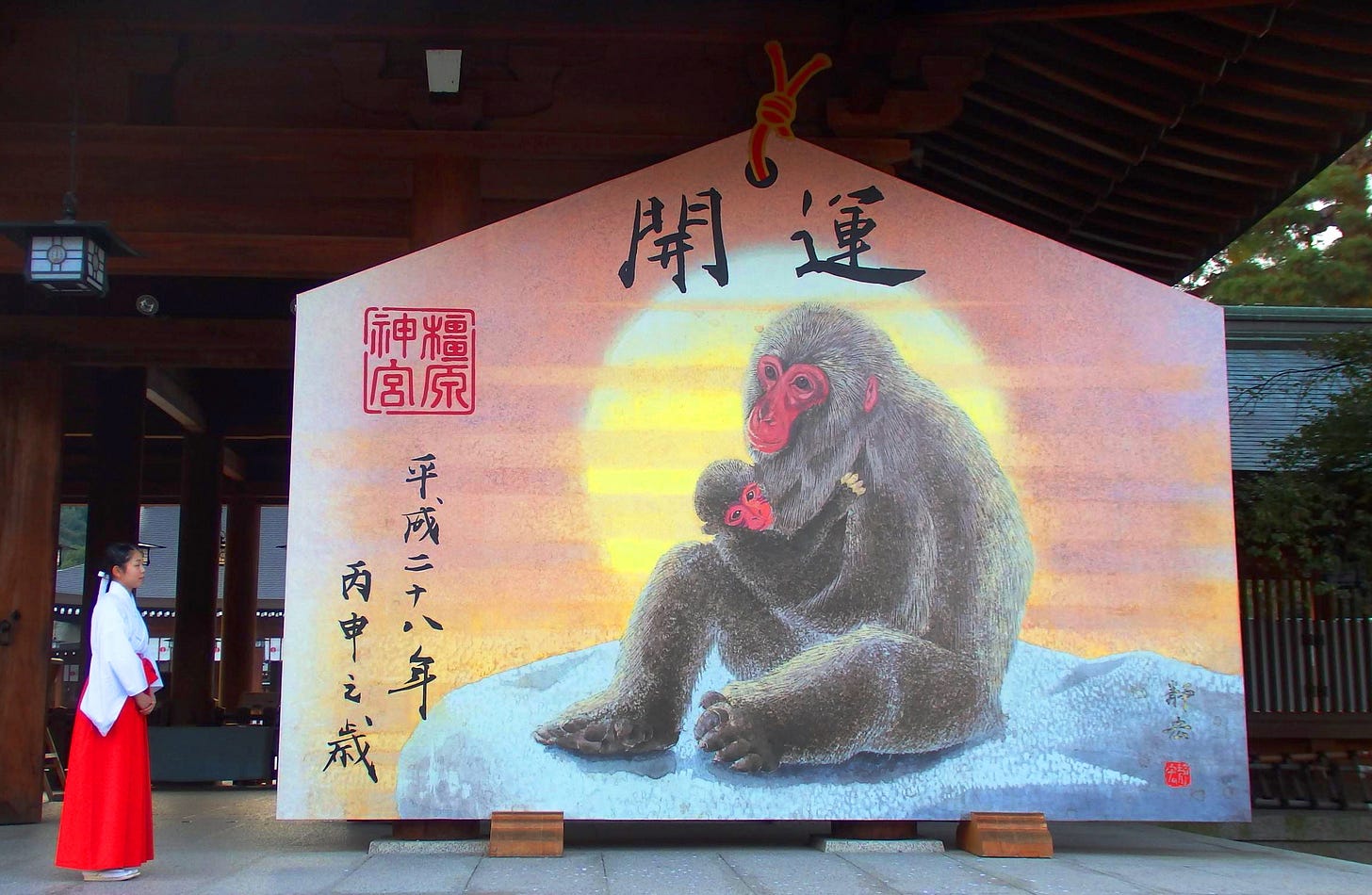

So it’s a substantial shrine somewhere. They’ve probably taken a break to and from the Osaka concert. He also plays in Yokohama and Akita. It wouldn’t be impossible to work out which shrine it is from the few background architectural clues. It would be great if it were the Kashihara Shrine in Nara, as that is associated with the Emperor Jimmu and therefore the festival mentioned above. Jimmu is the first Japanese emperor. A magical mythic character, not incomparable to King Arthur in some aspects, who founds the nation in 660 BC.

Léo “Ni Dieu ni maître/No God No Masters” Ferré is hardly likely to have been won over much by all that talk of the founding of empires and such. If he ever drank in the Napoleon Bar at the Akasaka Prince, I like to think he was smirking his way through the drinks at the strangeness of it all or possibly just opted for a different bar option altogether.

In 1987, it was the Year of the Rabbit. While looking at photos of Kashihara to see if I could confirm if this was the location - it’s not, hélas, it’s almost certainly the Heian Shrine in Kyoto - I noticed that in recent years it has been the custom there to display a massive ema/絵馬 of the zodiac year. Votive plaques on which you write prayers and wishes. Oh, I thought, if only he had visited for the Year of the Monkey.

LAST NOTE: If you’d rather have read a great essay about Baudelaire, with mention of Léo Ferré in passing, rather than its opposite here, I can well recommend Ian Penman’s review in the LRB of Late Fragments, translated by Richard Sieburth